In 1271 when Marco Polo left Venice at the start of his journey to the land of the Kublai Khan, there was another Marco that traveled with the expedition.

The Grand Canal

The Other Marco, also known as TOM in this blog, grew up near the Grand Canal that wound its way through the middle of Venice. Little did he know that he would one day travel along another Grand Canal far from the one he knew at home.

This was the Grand Canal of China, stretching for 1800 km from Khanbaliq [Beijing] in the north, down to Hangzhou in the south as the longest artificial river in the world. According to historians this massive project was probably started as far back as 600 BCE. It was mentioned in 330 BCE by a diplomat called Su Qin. Naturally it began as a series of canals near natural rivers and was not linked up as a continuous waterway for centuries. It took five million labourers, men and women, to eventually complete the task in the years 604 to 609 CE.

Besides its sheer size, TOM was fascinated by the system of locks on the Grand Canal that lifted the boats and barges on the water over the hills that obstructed their progress. There were of course no locks on the Grand Canal in Venice where he came from.

Earlier locks were known as Flash locks, basically a gap in the wall of a weir that dammed up the ‘higher water’ of the river or canal. This opening was controlled by a single gate. A boat going down stream would position itself near the entrance of the gate to be opened and wait to be propelled through it as if shooting a rapid. This operation was extremely dangerous as the boats could slew sideways and be rolled over. Up-stream boats had to be pulled through the out-flowing gate by ropes around a capstan [winch] positioned higher up the waterway.

Rereading this last paragraph, I realized what was troubling me. The ‘single gate’ needed more information so I returned to the references I had been consulting. After much more searching, I eventually understood just how complex that single gate’s mechanism was. One cannot simply slide or swing a gate across a gap gushing torrents of water to close it and then opening it again later when the pressure of the high water was pressing against it. The answer was to construct a temporary barrier across the gap to allow the water to rise up behind it, and then to quickly dismantle the obstruction to let the boat ‘flush’ through. A formidable task to be sure.

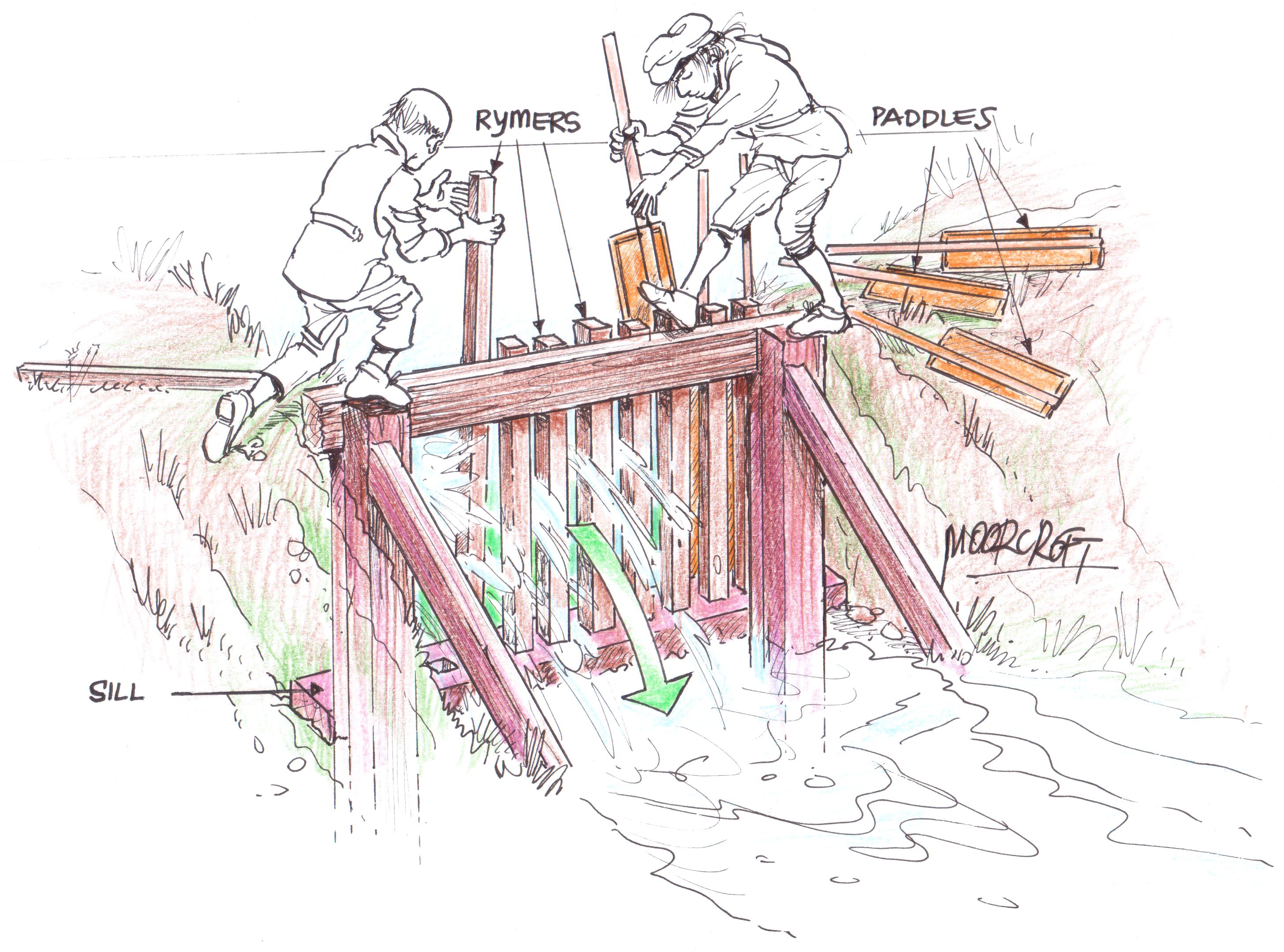

Flash Lock Gates.

A huge heavy beam, with evenly spaced square slots cut into it, was securely fixed into the canal bed where the ‘gate’ would be positioned. This beam became known as the Sill. Two equally sturdy posts with bracing arms were also permanently fixed on either side of the Sill with the weir wall closing against these posts.

This diagram shows the steps in erecting a flash gate only, the real barrier was of course a lot wider.

The material to build the temporary barrier lay on the wall ready to be used. Another sturdy beam as long as the gap was wide, was placed and held against the top of the two side posts. Positioning this beam and then quickly removing it must have taken skill and strength. Next a series of square timber poles called Rymers, were slotted into the holes in the Sill, resting against the upper beam and being held in place by the water’s force. This framework looked like a giant comb with water gushing between the gaps. To close these gaps, flat timber panels fixed to longer poles for ease of handling were slid down to block the water flow through the rymers. The water behind the now closed barrier would rise and the boat needing to go down-stream would be positioned nearby.

When sufficient water had been damned up, the Flash barrier would hurriedly be dismantled allowing the waiting boat to be shot through the opened gap by the flood of released water. Not for the faint-hearted.

The need for greater safety saw the invention of the double gated pound lock in the tenth century CE. Having two gates the boat was impounded [trapped] on the level water between them, giving rise to the lock’s name, ‘pound’. The vessel would enter through the first gate and be stopped by the second one. The first gate now closed behind the boat and the water in the lock was either pumped out, lowering the boat to the lower water level, or more water was added raising the water level in the lock and thus lifting the boat to the higher water level behind the second gate!

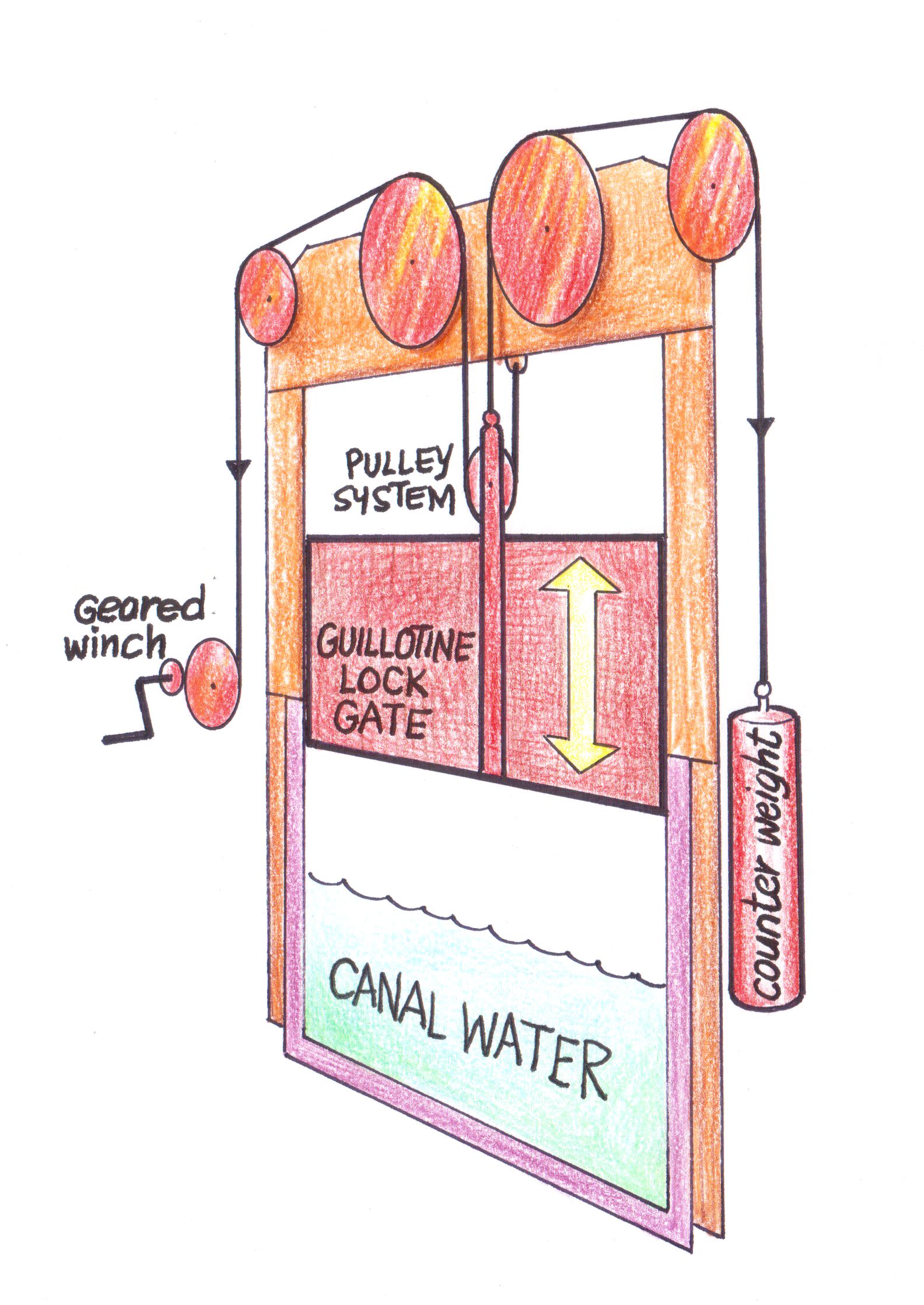

Guillotine Lock Gates

The first pound lock in Europe was built in Holland in 1373 – like Chinese locks it had Guillotine gates, designed to drop down like a castle’s portcullis [or guillotine] to shut off the water flow. This system replaced the flash locks and quickly spread throughout Europe

The biggest drawback of this type of gate was the immense effort required to overcome the weight of the gate when lifting it up high enough for a boat to pass beneath it. As the diagram shows, a system of geared pulleys, wheels and a counter-weight eventually overcame that problem. The rapid wearing down of the gate edges as they slid up and down in their vertical channels was also a problem. Yet this design continued for hundreds of years.

The Mitered Lock Gate

In 1487 Leonardo da Vinci invented the miter system, and changed the opening and closing procedure of lock gates forever, vastly improving on everything that was used before. Because each gate was longer than half the canal width, they slotted together when closed to form a right angle pointing up-stream. The water pressure pushing against the gates, increased the water tight properties at this joint.

The first lock with mitered gates was known as the San Marco lock, built in Milan in about 1500 to join two canals of differing levels. Modern locks on the Panama canal and other huge systems world-wide, still use the miter lock method.

The diagram above has a section removed from the body of the lock to show the difference between the high water mark on the left side and where the water level drops to on the right side.

So much for locks and their history, it is time for MONSTERS!

Here I must apologize that I have not had time to draw a new creepy monster for this even numbered posting, so I am cheating a little by giving you a photo of a goofy looking monster I built many years ago for a theme park. As we have been talking about locks, perhaps we can call it the Lockless Monster with apologies to the fabled Loch Ness Monster of Scotland.

Have a super monstrous time till we meet up again in TOM#17 [Tom#18 for the next monster]